With Halloween fast approaching, and Trick or Treat Weekend at the Ohio Renaissance Festival just around the corner, all sorts of shrieks and screams are waiting for you to enjoy! As we participate in this modern season of the supernatural, do you ever wonder what the Elizabethans believed in? Did they have a love for terrifying stories the same way we love horror movies? What local superstitions held sway as dusk fell and dark clouds drew close around the silvery moon? What better time to look at the history of dark folklore and fear than with this week’s blog!

A Little Perspective

It is important to understand that while there were many harvest festivals and church holidays, Halloween was non-existent during the Elizabethan era. They did have All Hallows Eve (Nov 1st), which was specifically a Catholic religious festival dedicated to honoring the apostles, saints, and martyrs. Now given the trouble the stoutly Protestant Queen had with Catholic revolutionaries, it should come as no surprise that the festival was abolished under her rule and the traditional bells no longer sounded to commemorate the dead.

However if history has taught us anything, a governing body has no control over what the people believe in their hearts and souls. Folklore, tall tales, spooky stories, and local legends have always had a place in society and the Renaissance was no exception. Elizabethans believed in spirits, both benign and malevolent, and that these entities existed in close proximity to humanity at all times. They believed in the forces of the old world around them, and to their minds it felt only reasonable to take precautions against such powers.

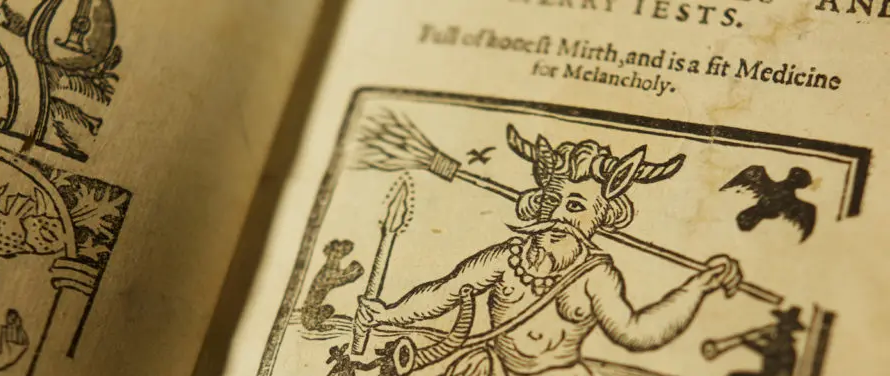

Witches

To the average folk of the 16th century, witches were a very real and very dangerous threat. Elizabeth herself brought into law “An Act Against Conjurations, Enchantments, and Witchcrafts.” in 1562, which made acts of witchcraft that resulted in someone being harmed or destroyed punishable by execution. Witches were blamed for any and all manner of troubles, from a bad harvest to the Bubonic plague, and used their powers to bring harm to all good Christian folk. Of course, the fact that most of those prosecuted for witchcraft were people who lacked protection under the law (elderly, unmarried, foreigners, mentally ill, vagrants) and could be easily gotten rid of didn’t seem to enter into the equation. Not when you consider that witches could, according to superstition, change into animal forms, curse one’s livestock, or give people terrible illnesses.

Fairies

Capricious, unearthly beings with an utterly inhuman sense of morality, the fairies of Elizabethan England were far from the lovely creatures born of nature we see them as today. Protestant folk associated fairies with the devil, their tricky nature making them creatures of deception and thus, aligned with evil forces. Churches would ring their bells when a bay was born, as the sound was said to frighten off wicked fae who might take the infant and exchange it with a Changeling. It wasn’t until later in the Elizabethan Era, right around the same time as A Midsummer Night’s Dream was being touted on stage that the portrayal and public opinion surrounding fairies became less cruel and more mischievous.

Devils

In the minds of the people, the devil was not a metaphor or an existential threat, but a very real and present danger to one’s immortal soul. Satan was an affliction to humanity, and the cause of all suffering, which was plentiful and widespread for most of the general population. There were recorded cases of demon possession, the reasons for which include everything from an ‘irreverent’ tavern sign to associating with Catholics, to sneezing without saying “God bless you.” thereby allowing the Devil to enter your body through your mouth. Some even believed that Anne Boleyn had ‘the Devil’s Mark’, despite witchcraft not being among the charges that led to her execution. These beliefs, of course, only enforced the role of the clergy as essential to society.

Omens and Portends

You may find it surprising to learn how many of the Elizabethan beliefs in bad omens have continued on into the modern day. For instance, seeing black cats as a sign of bad luck was prevalent during this era, as witches and devils were thought to be capable of turning into animals, and cats were ‘known’ to be familiar to witches. Spilling salt or pepper was seen as inviting bad luck, mostly because these spices were considerably expensive at the time, and spilling them was wasteful. Oddly enough, it was considered good luck to touch the hand of a man who was about to be executed, but bad luck to walk under a ladder because it greatly resembled the gallows! Owls were considered to be portends of death and stirring a pot counterclockwise was thought to bring bad luck to anyone who ate the contents.

Protect Yourself

With so much evil in the world out to get you, it’s no wonder the Elizabethans sought out protections to keep themselves safe. For many the church provided a sense of security from all the wicked things of the world, man-made or otherwise. But for others, that wasn’t quite enough to leave one feeling safe. For example, during the plague (pick one), people would stuff their pockets with flowers because they believed the good smell would ward off the miasma that caused sickness. It was believed that the ‘seventh son of a seventh son’ held particular powers, and some were claimed to be ‘cunning men’ who would aid those in need with potions or charms. One might put a dead cat in the chimney or leave a jar filled with urine and pins buried at the entry of a house in order to ward off evil spirits.

While the superstitions and beliefs of the Elizabethan folk may seem contradictory, if one looks closer is it a colorful snapshot of humanity in all its counterintuitive glory. A poor woman telling fortunes for a threepence could be imprisoned, tortured, and executed for witchcraft yet at the same moment Queen Elizabeth herself could be having a private meeting with John Dee, her personal occultist, astrologer, and alchemist. While a priest stood at the head of the church, speaking doctrine against the devil and all its powers, a cunning man might have visitors from that very church come to him for aid regarding their cow that’s gone dry. It’s not so different from now, where even those of us who profess not to believe in superstitions and ghost tales take one day a year to celebrate the ghoulish glamour of the supernatural.