Green has always been a hopeful color. Green is a sign of life, a sign of returning abundance and change. The sharp clarity of a fresh bud rising from a barren branch. The scent of grass rising up from the wet earth and shuddering in the breeze. Green is about life. It’s about renewal. It is about the tenacity of the world to survive the harshness of winter and thrive as the winds change.

The Man – Maewyn Succat

St. Patrick’s Day in a religious sense revolves around the death of the Catholic saint himself. Mythos about him as abounded for decades but history is a bit more solid on the subject. To begin with, he wasn’t Irish at all. His parents were believed to be Romans in charge of the colonies of Britain around the 400’s A.D. Patrick was the name he took after becoming a priest but his birth name is thought to be Maewyn Succat. He was kidnapped from his home by pirates and brought to Ireland where he was forced into slavery for six years.

This was during the Iron Age, and Ireland was still a majority pagan colony, though Christianity had begun to spread out into its lands. During his captivity, Maewyn believed himself to receive a vision from the Christian god, telling him to travel to the coast where he would find a ship that would take him to Britain. He escaped his captors and indeed managed to return to his parents in Wales. Later, he would travel to France where he joined the priesthood and became a bishop. It was around this time that he was said to receive another vision from the Christian god telling him to return to the land where he had once been enslaved and to bring Christianity to them.

Patrick spent forty years preaching in Ireland. He once spent all of Lent on the top of Croagh Patrick (formerly Cruachan Aigli), fasting and praying at what may historically have been a site of pagan worship. He and his followers built monasteries and churches and because of this Patrick was posthumously hailed as the patron saint of Ireland for having brought Christianity to the masses.

The Immigrants

Long before the potato blight of 1845, the Irish had been immigrating to America. Charles Carroll of Carrollton, the sole Catholic signature on the Declaration of Independence, was of Irish descent. During the 17th century over 10,000 Irish came, over 8,000 of them as prisoners of war and indentured servants bound for the Chesapeake Colonies (Virginia, Maryland, parts of Penn. And New Jersey) following the Irish Rebellion of 1641 and the Eleven Years War. But it wasn’t until the Great Famine that lasted from 1845 to 1849 that the second wave of Irish immigration reached American shores.

The blight was caused by a water mold or fungus called Phytophthora infestans, which rendered the roots of the potato inedible. This, along with the oppressive and brutal domination of Ireland by the English forces, pushed the Irish into starvation. Like so many throughout history, they were forced to choose between the bleak prospects of their homeland and the unsure promise of a new home. Over a million Irish immigrants are estimated to have flooded into America only to find themselves unwelcome in a strange new world.

In 1847, the Choctaw tribe donated $170 (about $4,700) to the Irish people despite their own suffering during the forced resettlement known as the “Trail of Tears.”

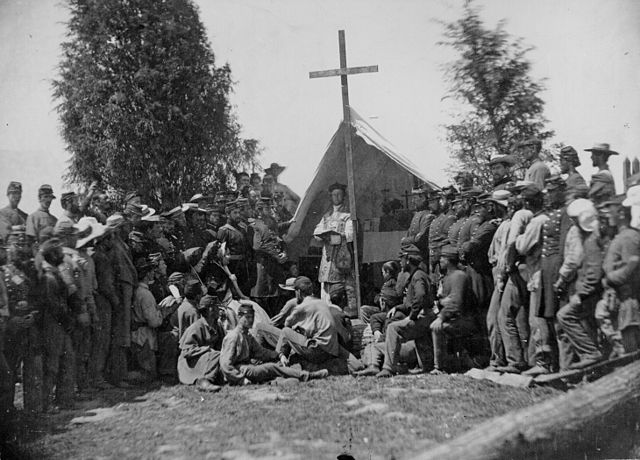

Catholics were considered undesirable in a virulently Protestant land. Some took off across the new world, seeking a home and eventually arriving in Mexican territory. At the time, this included most of the southwest from Texas to California and the people were staunchly Roman Catholic. Many Irish felt more welcome here than up north. So much so that they sided with Mexico during the Mexican-American War in 1846-1848. To this day Mexican/Irish relations are diplomatic, with several noted figured in Mexican history sharing Irish heritage.

For those who remained in the northern American states, life wasn’t going to get any easier for a while. America was at the tail end of a long and bloody civil war, and thanks to the Famine and long transportation across the ocean, much of the Irish immigrants were quarantined on Staten island due to typhoid fever and a cholera outbreak being a risk. As the Irish did begin to spread out, they favored larger cities where they could establish communities that would allow them some measure of protection and familiarity with their neighbor. To this day, many of those cities still have a large Irish population, such as Chicago, Baltimore, Boston, Detroit, and Cleveland.

It was not until the Emergency Immigration Act of 1921 (aimed at preventing Eastern European immigrants fleeing persecution from entering the country) went into effect that the Irish immigration slowed, the later newcomers moving into the community pockets their forebearers had established. By now the Irish-American had been born a thousand times over, and their unique culture had begun to blossom.

St. Pattie’s Day

While St. Patrick’s feast day has long been a staple of the Catholic church, providing a brief respite from the rigors of observing Lent, the first St. Patrick’s Day Parade was held in Boston in 1737 by a group of Irish soldiers in service of the English military. In 1762 New York City held its first SPD parade, and the tradition has grown ever since. As the presence of Irish America grew and became more expansive, public attitudes towards their presence slowly changed.

By the 1900s the Irish-American had become an influential and integrated part of American society. In 1962, Chicago first dyed its river green. This action, sponsored by the plumbers union, originally used fluorescent dyes, but those have long since been traded in for a more environmentally friendly powdered vegetable dye. The symbolic green hue was not actually associated with the auspicious day until the Irish Rebellion of 1798, until which time the traditional color was blue in association with the royal court. Irish soldiers at the time, in contrast to the British red uniforms, chose to wear green on the battlefield.

It may surprise you to know that up until the 1990’s St. Patrick’s Day was not a very secular festival. Pubs in Ireland still had to remain closed on March 17th in observation of a Catholic feast day. But as tourism became a necessary way of stimulating the economy, the Irish government reconsidered its position. In America many colleges have Spring Break right around this time, providing a much-needed respite after mid-terms. The festivities quickly became a way for people to celebrate not just Irish heritage, but a part of America’s cultural tapestry.

There is a reason we say that everyone is Irish on St. Patrick’s Day. And it’s not about our joint capacity to drink green beer and do shots of Jameson’s. It is more than the blood and the bones of those who came to this country before us. It is a heritage of welcome and capacity for goodness. It is a people who open their doors, offer you a pint, and tells you to take a seat. The parades will not happen this year, but the Irish spirit has proved itself tenacious in the most adverse of circumstance.

How to Celebrate St. Patrick’s Day at Home

As we remain in our homes on St. Patrick’s Day 2020, we have to look inwards for ways in which we can celebrate with our family. Even if the religious aspect isn’t as significant to you, this is a chance to reflect on the past and be proud of how far we can go together. So raise a pint, cry “Sláinte” (health in Gaelic) to your neighbors across the road, and wait for better days to come. In the meantime, take a few suggestions from us.

- binge 2 seasons of Derry Girls on Netflix

- hit The Secret of Kells & Song of the Sea on Amazon Prime

- Basics with Babish has an amazing Shepard’s Pie recipe well worth trying

- hide paper shamrock leaves throughout the house and give your kids 10 mins to find as many as they can! each leaf earns them a gold chocolate coin.

- Take ice cream, milk, peppermint flavoring, and green food-safe dye to make shamrock shakes

Get Your fill Of Celtic Culture at Celtic Fest Ohio 2020!

Celtic Fest Ohio is June 19 – 21. Experience the music, dance, food, drink, and unique shopping for yourself. See our brand new website for more information

Sources

Croagh Patrick, Westport in Co. Mayo – mayo-ireland.ie

History of St. Patrick’s Day – history.com

Irish-Catholic Immigration to America – loc.gov