Honour, riches, marriage-blessing,

Long continuance, and increasing,

Hourly joys be still upon you!

Juno sings her blessings upon you.

Willaim Shakespeare, The Tempest

These days we think of love and marriage as a somewhat nebulous concept. For some, it’s a deeply spiritual commitment that joins willing people together. To others, it’s more like one option among many, and to some, it’s not something they really think about. But for a long time, the definition and necessity of love have been up for debate. We’ve all heard of the now-infamous six wives of King Henry VIII and the countless flirtations of his daughter, Queen Elizabeth. While their lives may make for debauched tales of royal hedonism and recklessness, there was a lot more to it than that.

For many of the folks that lived in the Tudor period (1485 – 1603), courtship was the opportunity for a potential couple, (arranged or otherwise) to get to know one another and let their parents work out the details. The wealthy had property and inheritance to consider, as well as the long climb up the social ladder. Marriage could often be a political tool and a business proposition, however, the romanticized idea of a ‘loveless marriage’ was not as common as we like to believe. While it certainly did happen most parents wanted the potential couple to at least get along well and make for a good match. Also, the notion that extremely young women were frequently married off to aging older men was far less commonplace than we’d like to think. It was something of a scandal when Henry VIII, then 49 years old, became interested in Catherine Howard and made the barely 18-year-old his Queen despite the common age of marriage being around 21 – 24.

There was a great deal expected of a young man or woman before they were considered suitable prospects for matrimony. Most people did not get married until they had a bit of stability and a household of their own. It was considered very irresponsible to pursue a family unless one had the means and ability to maintain one. While parents or relatives might push for a good match between their prospective children, they were not supposed to force the two into a relationship should they find the other objectionable. For this purpose, matchmakers could be employed to find a suitable pairing with proverbs such as “Like blood, like good, and like age make the happiest marriage.” This meant that you wanted to find two people of relatively equal temperament, status, and age in order for a marriage to be successful.

Once courtship began, it was expected for the man to attend to the woman frequently, plying her with gifts. While the nobility and similarly wealthy could give some truly extravagant gifts (Robert Dudley gave Elizabeth 1st a jewel-encrusted white doublet as a New Years gift in 1575), those with lesser accounts might give something like bright ribbons, girdles, lace, and gloves to the woman of their affection. These trinkets were no small thing as they often assured the bride and her parents of his ability to take care of her and their future children. If these gifts were continually accepted and the two finally agreed to a betrothal, marriage usually wasn’t far behind. In fact, it was often so assured at this point that many couples began their physical relationship before the official ceremony actually took place. Despite the church’s prohibition on sex before marriage, approximately 20% – 30% of babies were born within 8 months of the wedding date.

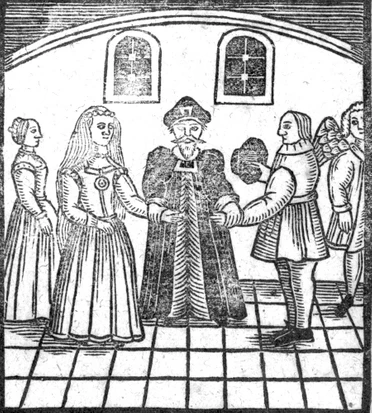

At this point, a dowry was under discussion. This was typically paid in goods and property as well as cold hard cash, which ensured that the couple had a good start to their new life together. Though the dowry was given to the husband there was also something called a jointure which ensured that should the husband die, his wife would be provided for by his family. Once everything was agreed upon and all was well a marriage could finally occur! This required not only a priest but two witnesses to vouch that they could have indeed ‘pledged their troth’ to one another, making the marriage valid. The priest had to go about ‘asking the banns’ which asked if anyone had any reason as to why the couple should not marry. This was not merely an objection, but more like providing evidence in court! If no one objected then the couple made their vows, the ring was on, and the marriage was almost completed.

While noble might have their court feasts, for the more common folk marriage feasts might involve the whole village. It was an opportunity to celebrate and relax, and it was not unusual for everyone to contribute towards the entertainment and food. This could carry on well into the night until at some point the guests would remember that the couple needed to fulfill one more requirement in order to make the marriage binding. They would escort the newlyweds to their home, often leaving ‘bride-ale’ with them to help ease any nerves, and leave them to enjoy their new life together.

All in all the English had a very practical mindset when it came to matrimony. It’s important not to look at this through rose-tinted glasses, as women were considered to be the property of their husbands and had few rights or recourse if the marriage turned out poorly. Though divorce could happen, it was rare indeed. Couples were encouraged “to marry first, and love after by leisure” in the hopes that this would prevent rash decision-making and poor choices. Good, long-lived matches were considered the result of effort and dedicated spouses who cleaved to the social expectations of the time. However, for all its problems, there were rare love matches and devoted partners who made it work.

Suggested Reading:

Sex in Elizabethan England, By Alan Haynes

How to Behave Badly in Elizabethan England, By Ruth Goodman

Sex, Love & Marriage in the Elizabethan Age, By R.E. Pritchard