The holiday season is a time of splendor. People turn out their best in hopes of bringing light into the darkness. Whether it’s a faith that the sun will one day break through the clouds or that a divine miracle can be visited on humanity, we all hold this time of year to a higher standard. We implore ourselves to be at our best and embody virtues such as compassion, generosity, and goodwill. Many of our modern Christmas traditions are stay-overs from the Victorian period and in fact quite German in origin, a by-product of Queen Victoria’s marriage to Prince Albert. Before this, Christmas was a rather raucous affair, one I strongly doubt we’d recognize when compared to its modern incarnation.

History

The Tudor era of England lasted from 1485 when Henry VII of the House of Tudor took the throne all the way through ’till the death of his granddaughter, Queen Elizabeth I in 1603. This time is well noted for political and religious upheaval, which often marks a shift in public observance and celebrations. During the reign of Henry VIII, England transformed from a Catholic country to a Protestant one. Many of the old masses were done away with and celebrations were altered to disassociate them with Catholicism.

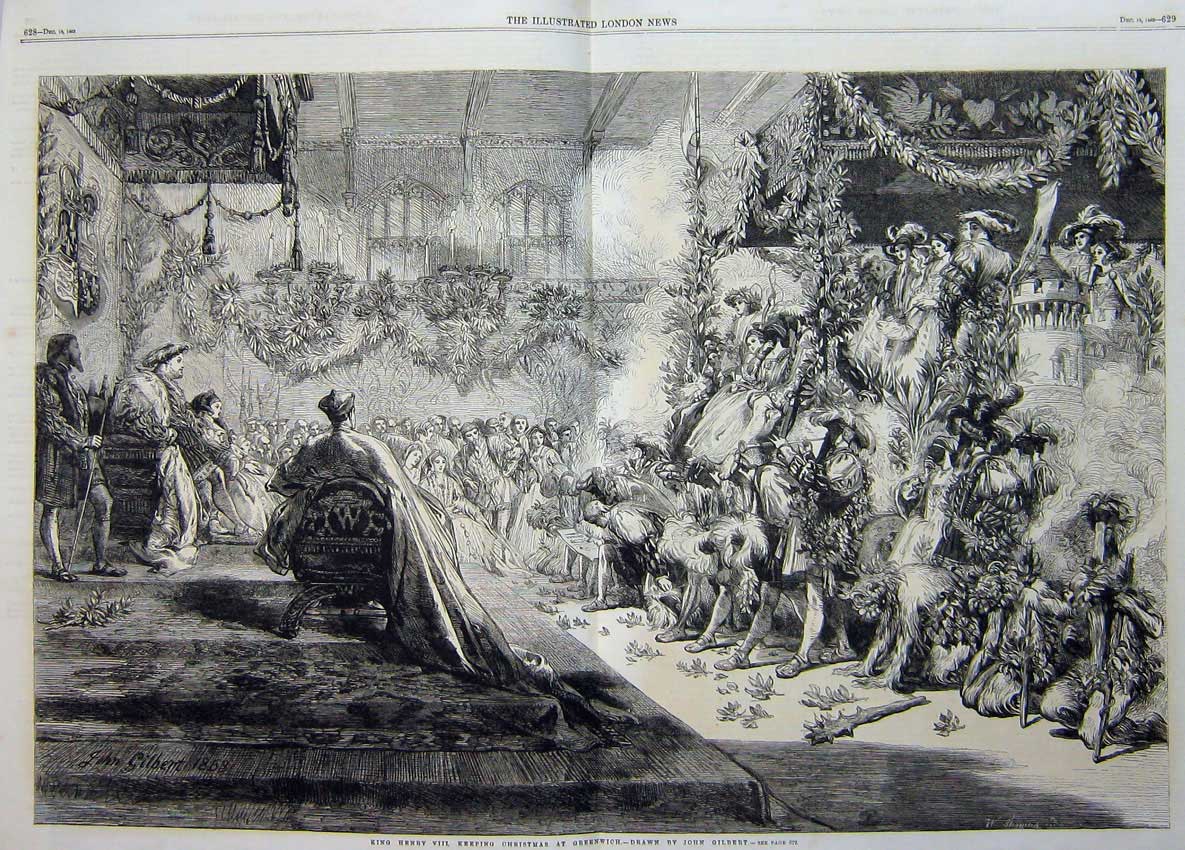

This did not seem to affect the passion people had for the season. Henry VIII was known for keeping the festivities with hospitality. Father Christmas was already a popular figure, although he may have been a great deal more disciplinarian than his modern counterpart! While Henry the VIII’s reign heralded the season with roast boar, turkey became popular during Elizabeth’s time as it was brought back from the ‘New World’. The celebration of Christmas was a twelve day event, beginning on Dec the 25th and lasting until Jan 6th, and was a time for merrymaking and revelry. Gifts were exchanged, not on Christmas morning, but on New Year’s Eve.

Many of these celebrations were the foundation for later traditions, which in turn trickled down to our modern Yule-tide enthusiasm. Looking back, it is easy to see how they took hold in the popular consciousness. So let’s see how you can add a little bit of the Tudor Christmas into your home this season!

Decorations

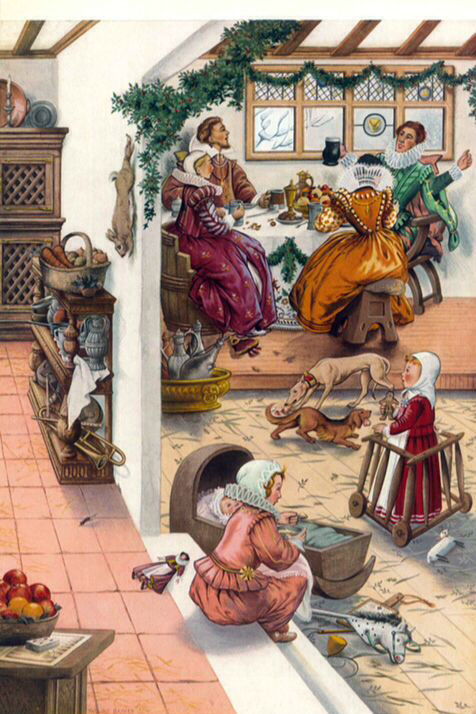

While the Christmas tree was not a staple in England until the Victorian era, it was customary to bring the brightness of the evergreen indoors to ward off the bleak winter. Vivid green decorations like holly, ivy, yew, mistletoe, box, and laurel would have been commonplace. A ‘kissing bough’ was decorated with mistletoe and even apples, giving us the per-cursor to our modern tradition of kissing under a sprig of this small plant. Garlands were hung to add cheer to a room.

Despite the Christian atmosphere, the Yule log remained a dedicated pastime for both king and peasant alike. The yule log originated among the Nordic pagans, where an entire tree was burned during their Yule celebrations. Likewise, the log had to be big enough to burn for the entire twelve days of Christmas and was believed to ward off misfortune and disease.

Pomanders were a popular staple for those who had the wealth to show off. Oranges were pierced with clove, bringing a spicy, citrus scent to the area and creating a cozy, warm environment. It’s important to remember that during the cold months, people were often unable to air out their homes, so a pleasant aroma like orange and clove was a welcome relief! Other dried fruits were used to add a splash of color to the décor, and candles were plentiful as they brought light to dark corners.

Food

Today many people celebrate the Advent (the 24 days leading up to Christmas) with a little calendar that gives tiny treats each day. In Tudor times, they celebrated by fasting for four weeks. Rich foods like eggs, meat, and cheese were off the menu. The more strict might abstain from alcohol (such as wine since ale and beer were drunk like water) and even desserts. While lavish feasts could only be afforded by the wealthy, Christmas day was a time to break open the larder and enjoy the fruits of your labors.

Goose and wildfowl had a reservation at the center of the table, often stuffed with one another until they resembled the rings of a tree when sliced open. The particularly wealthy enjoyed boar’s head dressed with herbs and made fit for a king’s table. Mince pies were a particular treat and were often rectangular, meant to resemble the manger in which Jesus had been born. In 1545, the ‘A Proper newe Booke of Cokerye’ gave instructions for how to prepare an excellent mince pie.

To make Pyes – Pyes of mutton or beif must be fyne mynced and ceasoned wyth pepper and salte, and a lyttle saffron to coloure it, suet or marrow a good quantite, a lyttle vyneger, prumes, greate raysins and dates, take thefattest of the broathe of powdred beyfe, and yf you wyll have paest royall, take butter and yolkes of egges and so tempre the flowre to make the paeste.”

A Proper newe Booke of Cokerye, 1545

Fruitcake was served as well as a boiled rice pudding stuffed with fruits. Vegetables were considered a poor man’s diet, but fruit was a sweet treat and used liberally. The rich spread their table with the finest, if not the healthiest, of heavy meals. Marchepane (marzipan) delights were created with the newest in fashionable table treats, sugar and tarts were welcomed additions to every plate.

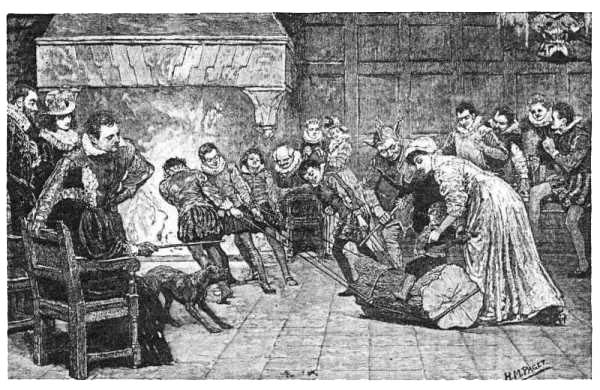

A special dish was served on Twelfth Night, which was comprised of dried fruit, spices and honey. Within the cake were a bean and a pea. Each guest was to take a slice and whoever found the prize amid the dense cake was rewarded by being the King & Queen for the evening and would lead the festivities. Hot spiced wine, mulled ciders, ale, and beer were drunk in mass quantities, surely invigorating the joyful spirit.

Revelry

Along with singing, dancing, and feasting the Tudors enjoyed many different entertainments during the Yule-tide observances. All work was expected to halt until Plough Monday, which was the first Monday after Twelfth Night, so that even the common folk could observe the holiday.

The Lord of Misrule was a prominent figure of the festivities. With traditions hearkening back to the Roman Saturnalia, it was the job of the Lord of Misrule to ensure that everyone was keeping the holiday merry and bright. This often involved pulling people into wild, drunken parties and getting into mischief. This was often someone from the area, or in the case of the court a noted noble. They would be decked in bells and ribbons and after being crowned, would have authority over everyone.

Pageants were popular entertainments, with mummer’s being a cheap way of keeping people happy during the twelve night celebration. Caroling became immensely popular, and children’s choirs became a pleasing diversion. Sports had been banned during the Christmas festivities (save for archery) while Henry VIII sat on the throne. But games such as gambling on dice and cards could always be found if you had money to lose.

Gifts were given on the New Year and, for the nobility, they often held a strong political significance. For instance, Catherine of Aragon once gifted her husband, Henry VIII, with a golden cup while he was attempting to divorce her. He rejected the gift but accepted the present from Anne Boleyn, whom he married the following year. It was expected for the monarch to return their generosity with a significant gift of their own.

There is little I have found regarding how the common people gifted one another. But since I can’t imagine what a farmer would need with a golden cup, I think the gifts would have been of a much more personal nature. Hand embroidered scarves, warm blankets, or other practical things were probably appreciated as much as any gilt candlestick or giant jewel.

This was a period of great change, but through it all, the celebration of the holiday persevered. Not just for its religious significance, but for its place among the people as a time of relief and joy they could look forward to during the dark months of the year. There has always been a winter festival, and in all likelihood, there always will be. Unless of course, you are Oliver Cromwell.

NEXT WEEK: Playing The Queen

We’ll look at the 3 most popular movies about Queen Elizabeth and discuss how the actresses take on the rule of one of histories most famous queens.

Sources

A Brief History Of Tudor Chistmas

Christmas at the court of Henry VIII by Alison Weir

Tudor Christmas Food by Sarah Bryson