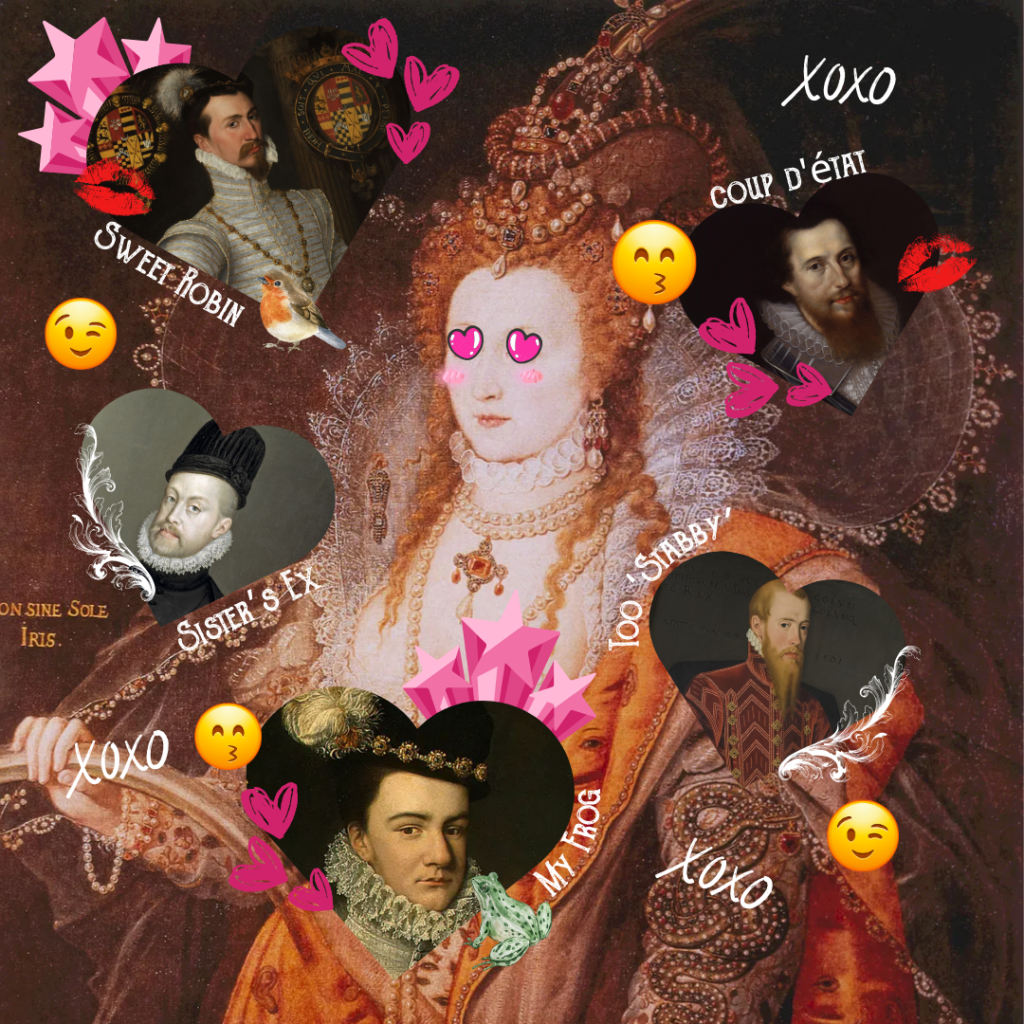

Following the death of her less-than-popular half-sister, Queen Mary I, Elizabeth Tudor ascended the throne in 1559 and became Queen Elizabeth I, Gloriana Regina, the sovereign queen of England and Ireland. Almost immediately following this momentous occasion came the inevitable question posed to every monarch sooner or later, but most especially Queens who ruled alone: Who would Her Majesty wed?

Since the death of Henry VIII, the English crown endured twelve years of dynastic turmoil concerning who had the right to sit on the throne and govern. Henry’s only acknowledged son, Edward VI, was only nine when his father passed and fifteen when he followed to the grave, leaving no heirs behind. Next came poor Jane Grey, thrust into the seat of power by politicians who did not want the throne to go to a Catholic queen, who ruled for nine days before being executed. Finally, Queen Mary was the first daughter of Henry VIII and his first wife Catherine of Aragon. Though she married King Phillip II of Spain and attempted to continue the Tudor dynasty, Mary would pass in 1558 without success, putting the only remaining Tudor, the Protestant Elizabeth, securely in power.

After over a decade of political shifts and weakening power, we can only imagine that the governing bodies of England were eager to avoid more mishandling in the future. The most effective way to handle this was, of course, to get the Queen wedded, bedded, and pregnant as quickly as possible in order to secure the bloodline and the future of the nation. This was easier said than done, as not just anyone could be presented as a potential suitor. Though Lizzie herself would keep her court guessing for decades, let’s take a look at some of the most likely candidates and why they failed to win Good Queen Bess’s hand.

Lord Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

Status, wealth, and international politics aside, every courtier with eyes could tell you that the Queen had a favorite, and his name was Robert Dudley. The two had known one another since childhood, and both had grown up enduring the lethal shifts in loyalty that could occur among the nobility. When Elizabeth was made queen, Dudley is said to have leaped on a white horse and ridden until he was by her side. Despite being already married to Amy Robsart, Dudley would spend a great deal of time at court in Elizabeth’s presence. Rumors ran wild that the two were carrying on a scandalous affair, as they were often seen dancing, riding, and whispering together. He was her ‘Bonny Sweet Robin’, and even during the turmoil of their relationship, they remained close until his death in 1588.

So why do we not have King Robert Dudley in our history books? Though it’s clear that Elizabeth adored him, Robert’s marriage was not the only reason she rejected him as a suitor. Robert’s wife passed in 1560 under suspicious circumstances, which led to tales that Dudley himself had orchestrated her death so he could pursue Elizabeth. Whether or not he was involved in his wife’s death had never been confirmed, but it did not help matters that the Earl of Leicester was already unpopular at court. His father had been part of the plan to place Lady Jane Grey on the throne, marking his family as traitors. Despite Elizabeth overlooking his objectively minor role in this plot, her continued shows of affection in the form of titles, responsibilities, and land tweaked the nose of many a man under her command. The final insult came when, after years of back and forth, Robert went and married Lettice Knollys, the Queen’s cousin, without permission. There was nothing to be done, and though the two childhood friends would eventually reconcile, the subject of marriage was off the table.

King Phillip II of Spain

Phillip II ruled as king of Spain from 1556 – 1598. A staunch Catholic monarch, Phillip’s desire to maintain the power of the Holy Roman Empire was resolute. His father arranged the marriage to Phillips’s maternal first cousin, Mary. Yes, the very same Queen Mary I, half-sister to Elizabeth. From all sides, the marriage was a political alliance, not a romantic one. Steps were taken to keep England from leaning too far into Spain’s control, though Phillip and Mary were considered joint rulers of England and Ireland while they remained wedded. However, Phillip’s concerns were largely preoccupied with matters outside of England and his then-wife. Phillip had his royal hands full between waging war, stamping out rebellions, and navigating the complex authority of what was then Spain’s elite.

Given that the first thing he did upon her death was offer a marriage proposal to the newly crowned Elizabeth, one could assume that Phillip was a shrewd man who sought to keep his position in England as well as maintain a Catholic stranglehold on the land. So why did his efforts fail? For one, Elizabeth was a strong Protestant with no desire to maintain the religious fervor that had made her sister so unpopular. For another, foreign marriages were to be approached with caution. England was not fond of the Spanish or the French, and many politicians were worried that marrying their bright young Queen to a Spanish king would cause an upheaval. The fact that he was her sister’s widower did not help matters and would only have added to public scandal.

Francis, Duke of Anjou

Born in 1555, Hercule was the son of King Henry II of France and Catherine de’ Medici. His namesake was less than applicable, as he had a deformed spine and a case of smallpox at age eight left his face badly scarred. As the youngest of his siblings, it would take the death of one brother and the rise of another to put him in line for the throne. It would not be until the death of his brother Francis II (husband to Mary, Queen of Scots), that he would take on the name Francis is in honor. Much to the distaste of his parents, Francis was a supporter of the Protestants, although himself a Papist, joining his lot in with the prince of Conde during a Huguenot rebellion that forced Henry III to sign a treaty in 1576 called the Edict of Beaulieu. This treaty gave land and titles to many prominent Protestant supporters, shifting the balance of power in France and making Francis a Duke. Perhaps this is what made him acceptable as a potential suitor to a then forty-six-year-old Queen Elizabeth.

At twenty-four years old and an ardent suitor, Francis must have thought himself a tempting prospect on some level for him to be the only foreign suitor to court Elizabeth directly. She was said to be fond of his attention, allowing the marriage negotiations to continue despite vigorous objections from her advisors. It was felt that the English people would never accept a French Catholic as a King, much less one whose family was heavily involved in brutal acts against the Protestant Reformation. However, Elizabeth seemed determined to proceed, even sending Walsingham to negotiate a treaty for an Anglo-French alliance. But France wanted a marriage first, and Walsingham had been told to get the alliance before a marriage could proceed. Between this and the ardent objection of her Privy Council, Queen Elizabeth would eventually say goodbye to the Duke of Anjou in 1581.

Prince Eric of Sweden

Intelligent, ambitious, and artistically skilled, Prince Eric was born in 1533, the son of Gustav I and Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg. He was well educated in his youth and apparently popular among the people as he was referred to as both the ‘chosen king’ and ‘hereditary king’ during his public appearances. There was some source of tension between Eric and his father, Gustav, the crux of which may have been his proposal to Queen Elizabeth. He was even preparing to visit her when news of the king’s death reached him, and he returned to Stockholm to begin his rule.

While this was not the end of his interest in Queen Elizabeth, it would soon become irrelevant. Eric’s reign was marked by political turmoil, as well as increasing evidence that the new king was mentally unstable and prone to violence. Though his expansions resulted in Sweden becoming a noted powerhouse by the 17th century, his paranoia and actions against his own people would lead to his downfall. In 1567, Eric was directly involved in the bloody murder of five members of the Sture noble household, including Nils Svantesson Sture, whom he personally stabbed to death. This was the last straw for the persecuted Swedish nobility. Eric was incarcerated and legally dethroned in 1569. After at least three documented attempts to free Eric and put him back in power, Eric died in 1577. It would not be until modern forensics were applied that the cause of death was discovered to be arsenic poisoning.

Robert Deveraux, Earl of Essex

It’s no secret that Her Majesty liked her suitors to be well-educated, charming, and even a touch brash in their devotion to her. However, there are few romantic entanglements that are as full of drama and betrayal as the romance between Elizabeth and Robert Deveraux. By the time Robert was born in 1565, the queen was already thirty-two years old. The son of the queen’s cousin Lettice Knollys by her first husband William Deveraux, young Robert was only thirteen when his mother remarried none other than Robert Dudley. He gained some political favor in court thanks to his military service and his father’s clout, giving him the opportunity to gain Elizabeth’s attention and affection. Like the Robert before him, the young suitor would soon discover that getting Her Majesty’s attention and keeping it were two very different things.

By this point in Elizabeth’s life, the question of marriage and childbearing was moot, if still occasionally asked about. She was now in her late fifties, a formidable monarch who had kept England safe and prosperous for decades. It may be that she wanted to rekindle the spark of youth, or perhaps she wanted to keep an ambitious young man close enough to watch. Robert was heaped with titles and revenue sources like his stepfather, which he received treated with somewhat less reverence than he ought. The young favorite was even warned not to offend the queen, and it’s said that at one point during a heated council meeting, the Queen cuffed young Robert, and he had to be stopped from drawing his sword on her.

Following a series of direct disobedience from his sovereign queen, his stupendous failure as a governor of Ireland, his arrest, trial, and finally, his disastrous attempted rebellion, Elizabeth could no longer let favoritism spare her hand. Robert Deveraux was arrested, tried for treason, and executed in 1601.